Humankind has a long history of trying and failing to “fix” language. What can Benjamin Franklin, Esperanto, and A Klingon Christmas Carol teach us about how language affects us? And for the thousands of indigenous languages at risk of extinction, how can the knowledge they hold be preserved, protected and revitalized? Featuring:

- Arika Okrent – Author & Linguist

- Stephanie Witkowski – Executive Director, 7000 Languages

- Daniel Bögre Udell – Founder & Executive Director, Wikitongues

- Renata Altenfelder- Global Executive Director, Brand & Marketing at Motorola Mobility.

Episode Transcript

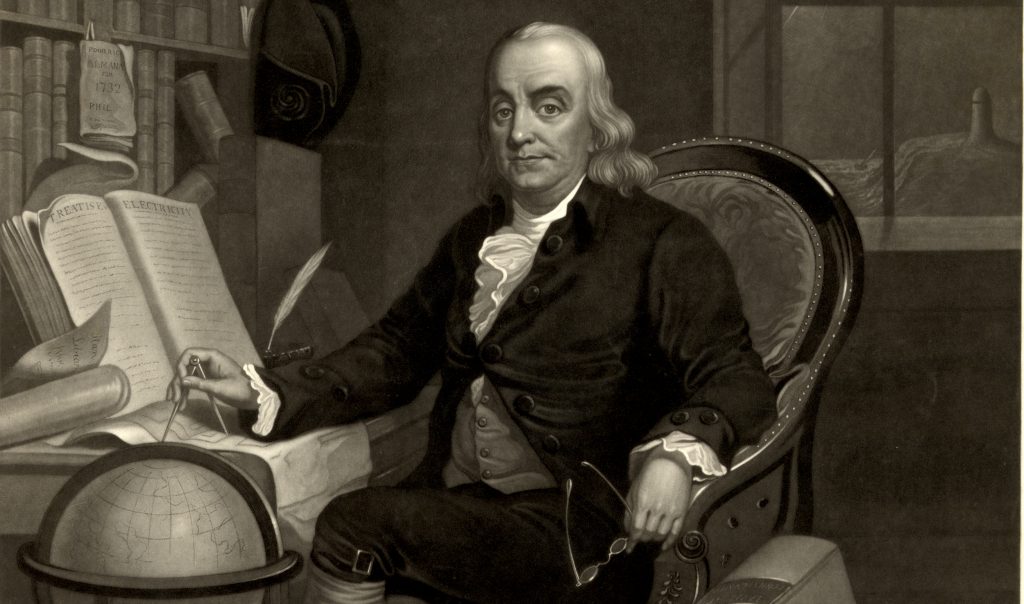

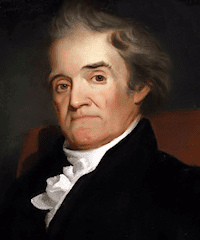

There’s at least one thing we know Benjamin Franklin wasn’t good at. Resting.

It’s 1779. The dust is still settling on the bloody revolutionary war, the streets of Philadelphia are bustling as the heart of the newly formed United States of America. Ben Franklin, at the spry age of 73, decides it’s about time he does something with his life and declares war on a new enemy.

Bad Spelling.

Because what good is freedom if your neighbors think Philadelphia is spelled with an “f”?

There was some recent success for big revolutionary ideas that aim to improve on existing models. So what was Franklin’s solution? A new alphabet. An American English alphabet that would do away with the frivolities and messiness of English in favor of a more refined, logical, and intuitive approach.

Benjamin Franklin’s Failed Alphabet

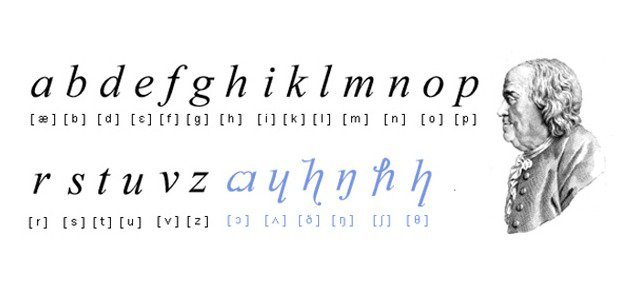

First order of business: cut the fat. C, j, q, w, x, and y would be voted off the island and replaced with newer, sexier letters. Letters for a new generation. The Pepsi to English’s Coke.

Some new letters would represent blended consonants like the “th-” sound in “think” or “there goes Ben Franklin, the guy who publicly shamed my son for spelling Philadelphia with an “F”.

Other letters brought new vowel sounds so the existing vowels weren’t asked to wear so many hats. The “uh” sound in “umbrella,” for example, would get its own letter, represented by what looks like an upside down “h”.

Franklin first proposed the alphabet in 1768, but put it on hold as tensions with the British boiled over. Also, it seems nobody was particularly interested in Franklin’s crusade against misspelled words and silent letters. That is, until a young writer and educator by the name of Noah Webster …came to Franklin with similar ideas of his own.

In 1786, Webster was working on a book of American English, full of grammar lessons and pronunciation techniques. He shared his work with Philadelphia’s most famous and adored man – Dr. Benjamin Franklin, now 80 years old. Webster was 28.

In sharing ideas with one another, they quickly found common ground.

“”Knock” starting with a silent “k”? Yes, quite preposterous!”

“C sometimes sounds like a “k”, and sometimes an “s”? This is both chaos and a circus.“

“Piece of pie and world peace, flour for baking and a flower in my garden?!”

To Franklin and Webster, homonyms and homophones were practical jokes and simply unacceptable. That’s when Ben Franklin poured himself a cup of tea, read The Declaration of Independence by candlelight, and went to bed. Because he was 80…

No, of course he didn’t. Franklin dug out his old alphabet to prove to the young whippersnapper that he might just have the answer to their language woes. The print blocks with his new proposed letters had collected dust for 7 years, but perhaps would have better success in Webster’s hands.

They did not.

Built on Franklin’s alphabet, Webster’s campaign for spelling reform failed to take hold in the minds of a new American public who saw it as too complicated to learn. Print blocks would need to be changed. Old books would be rendered obsolete. Plus it turns out that being at war for 8 years is…exhausting for most people.

Franklin died in 1790, and Webster carried on. Each version of his system compromised a bit more with what the American public was used to. First he ditched Franklin’s alphabet and tried new, more logical spellings using the existing alphabet. No redundant “double letters” like the “Ts” in…letters. No double vowels like the “e-a” – so words like “please” become p-l-e-z. Everything should look exactly as it sounds. That didn’t work.

Then he tried eliminating only silent letters. Surely we can all agree that words like climb and crumb have no need for the B at the end, right? Wrong. Old habits die hard and change sucks, Mr. Webster.

While the spelling revolution was not a success, it did lead to Webster’s most famous work: The American Dictionary of the English Language. Nothing like it had existed and its 70,000 words became the new standard for educators, authors and newspapers across the country, including a few new spelling victories.

What we now consider differences between British English and American English…multiple spellings of words like color and favorite – either with / without a “U”…had long been considered interchangeable… Until Noah Webster’s dictionary solidified the “u-less” “simpler” version as the American version. The Brits followed suit claiming versions with a “u” as correct English, starting a long tradition of red squiggly lines in Microsoft Word and confusion between American and British colleagues about whether “personalization” should be spelled with a “z” or an “s”. And whether z itself is pronounced as zee or zed. Let alone what the hell football means.

A tradition alive and well with my Kin + Carta colleagues across the pond. Which is our seamless segue to saying – hello and welcome to Look Both Ways! I’m Scott Hermes, and I’m your host.

Look Both Ways is a podcast about experimentation, world-changing ideas, and the willingness to get things wrong. Each episode follows a two act structure: First, an unsung failure of the past. And second, an unsolved challenge of the present. The show is made possible by Kin + Carta, a digital transformation consultancy who exists to build a world that works better for everyone.

On today’s episode: Language.

In Act 2: what is lost when languages die? And can technology help revitalize the culture, tradition and knowledge embedded in languages at risk of extinction? We’ll hear from Daniel Bögre Udell of Wikitongues and Stephanie Witkowski of 7,000 Languages. We’ll also talk with Renata Altenfelder, Global Brand Director at Motorola Mobility, about how they’re making their operating system more accessible to communities often left behind by the tech industry.

But first up: the fascinating failed attempts at invented languages, also known as constructed languages, or con-langs. Linguist Arika Okrent (Air-ik-a O-krent) helps us uncover what they can teach us about human creativity, the bizarre nature of language, and how the words we use affect how we think. Because as we’ll see, Ben Franklin’s impulse to FIX language is by no means a new one.

John Wilkins & The Language of Truth

The graveyard of proposed and failed “invented languages” is more vast than you might think, and while the thousands of documented invented languages vary greatly, they all have at least two things in common:

- They make Ben Franklin’s desire to change a few letters seem perfectly reasonable.

- They’re all born from a deep belief that language is messy and therefore should be fixed by, of course, the ingenuity and sheer will of the human mind.

Arika Okrent is the author of “Highly Irregular” And “The Land of Invented Languages.” Whether she intended to or not, she’s become the de facto expert on the aforementioned invented language graveyard, and was kind enough to take us on a tour of all its weird, fascinating glory.

ARIKA:

Well, I started looking at these projects as a linguist with total derision. You know, who tries to make up a language? First of all, that never works. Second of all, what makes you think you could do that when, if you study language, you know how complicated it is.

SCOTT:

In 17th century England, a man named John Wilkins felt he was up to the task.

He ALSO felt that English, and any spoken language for that matter, could do better.

Wilkins thought that language failed us because words don’t inherently communicate anything. For a child to learn that the word “dog” refers to the canine animal that walks on four legs and barks at its own shadow, and likes chasing tennis balls…you simply have to memorize the association. The word dog itself doesn’t actually help you understand its meaning.

For Wilkins, the problem was that words could mean too many different things. The word “clear” could mean that something was understandable or coherent. But it also could refer to the physical transparency of glass. To call the sky clear meant that it was without a cloud, but to clear an obstacle meant to go over something.

To Wilkins, the fact that the word clear was itself so UNCLEAR was nonsense and needed to be fixed at once. The TRUTH is what mattered, and words should express a single, CLEAR truth about a concept. He was also a man of science, and wanted to make scientific thinking more accessible to the general public, and more easily shared around the world. Ambiguity of meaning was slowing it all down.

Can Language be Engineered?

Surely there’s a better way, Wilkins thought. He took inspiration from an important new breakthrough in scientific thinking.

ARIKA:

It will be like using this new invention called mathematical notation, which was new. It was “Wow, we can express these mathematical concepts with variables, and symbols, and anyone can understand it, no matter what your language is, doesn’t matter what language you speak.” This is the truth. There on the page. So let’s do that and make that kind of mathematical notation, but it’ll be language and we can say everything with it.

For thousands of years, there was no plus sign, no minus sign, no symbols for multiplication, no equations. The concepts existed, but they were expressed in words. A plus sign doesn’t leave room for interpretation. So John Wilkins thought, what a beautiful thing! Why couldn’t language work the same way? Why couldn’t the word dog be expressed as a sort of….equation? Where each individual symbol contributes to a singular, specific truth.

SCOTT:

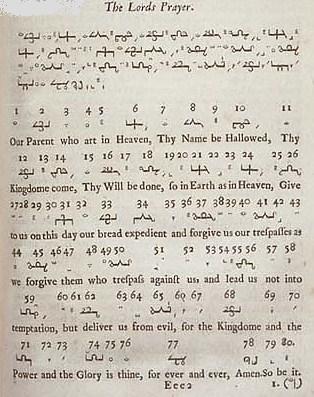

Wilkins’ language became a series of symbols to work exactly that way. Every shape had a specific meaning. “Dog” would have been pronounced as “Zita” Z-i-t-a. Each sound points to a different characteristic of a dog. The “Zi” sound means the word belongs to category XVII (17) of BEASTS. The “ah” sound at the end meant a bigger but docile beast…and the “t” sound in “Zita” meant subcategory V (5) of…

ARIKA:

Oblong headed beast. So you, you distinguish it from cat, and which is round-headed, or you have to get to the truth of everything, you have to also distinguish it from what it’s not.

Let’s say we need a word for you know, butter or something? Well, what is butter? Are we going to focus on the way it’s made? Or what it tastes like? Or what the shape is or what we use it for? Then you start running into trouble. Because it’s a lot harder than you thought to determine the exact meaning of every word you might want to use or every concept you might want to use.

SCOTT:

“Piece of cake.” Wilkins thought. All I have to do….is map out and categorize every single thing in the known universe. Which is exactly what he did.

ARIKA:

He sat down to make a map of meaning, a map of all the concepts in the universe of giant tree diagrams basically, of where everything fit.

Wilkins called his system a “Real Philosophical Language.” In her book, Arika demonstrates just how thorough Wilkins’ system was through a colorful and frustrating journey to figure out how to say the word “shit.”

It’s an amazing document of what the 17th century English person thought of the world and where everything fit. But it didn’t make a usable language.

Because if you want to say anything, before you choose your words, you’ve got to decide what exactly you want to say. And we don’t do that when we talk. We discover what we’re saying, as we’re speaking or as we’re writing, we don’t know exactly what we want to say before we pick the words. And that’s what speaking logically makes you do. It’s like if you had to write computer code spontaneously to get meaning across. And that would take us a lot longer than language does.

SCOTT:

As all of my fellow programmers know, “spontaneously writing computer code” is the only way to do it.

Void main(){printf(“I am coding spontaneously. Woo hoo!\n”);}

John Wilkins may have been one of the first to pioneer this hyper-logical approach to language, but he was far from the last.

Arika says the reasons most invented languages fail to catch on reveals something very important about what language is, and what it isn’t.

Because if you want to say anything, before you choose your words, you’ve got to decide what exactly you want to say. And we don’t do that when we talk.

Arika Okrent

ARIKA:

it’s not just a way of packing up a message and sending it along to someone else….The messiness of language gives it the flexibility that we absolutely need in order to be able to use it.

We have to be able to talk about things that we’ve never seen before, that have just come along new events, new technologies, we don’t freeze up and say, ‘Oh, how can we talk about this?’ We just keep going and invent words on the fly, or we stick endings together, we make new sentence structures when we communicate. And that makes language messy as it develops.

But messiness doesn’t sit well with people who need to solve problems in order to feel useful.

ARIKA:

A lot of language inventors, through history during this project had been kind of megalomaniacs. They think they’re the first one to think of this idea, which they don’t know they’re not. And then they think they have the brilliant solution, which they don’t. And they’ve if they push it out they think everyone should pay attention to them because they are genius, and because their ideas are so perfect.

…But Zamenhof didn’t start that way.

The Hopeful Language

SCOTT:

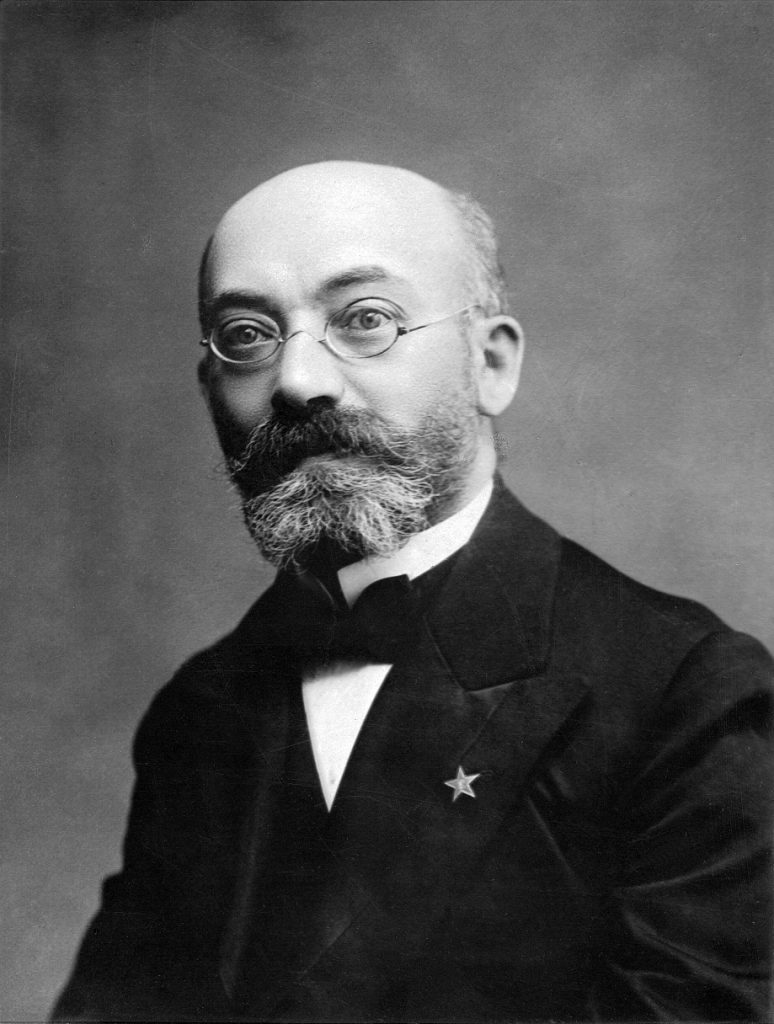

“Zamenhof” is Ludwig Zamenhof, the polish ophthalmologist and inventor of the most widely spoken invented language…the one you’ve likely heard of if you’ve heard of any: Esperanto.

First published in 1887, Esperanto was designed around the belief that language barriers were the root of conflict around the world, and that if Esperanto became everyone’s second language, clear communication would be possible and world peace would prevail.

So his ambitions were certainly just as lofty, but Arika says part of Esperanto’s success can be drawn back to Zamenhof, its creator, doing what others couldn’t. Letting go.

ARIKA:

Zamenhof let the community do the language and didn’t didn’t fiddle with it too much. And also the language itself was very bare bones. Here’s the 16 rules, and here’s a bunch of word roots. And there weren’t a lot of rules so that a person could speak it differently.

SCOTT:

Those “roots” were what made Esperanto tick, and supposedly what made it easier to learn than any other language.

ARIKA:

So the roots would be either from Germanic or from Latin, kind of mixed up and the word for and he chose from Greek and he chose some words from Yiddish and it was supposed to be a sort of mix, but also very, very easy to learn because no irregularities so no irregular past tense, the verb is always inflected the same way the the words you learn this group of root words and then you learn this limited set of endings, you can stick on them and then you go and you don’t have to learn the exceptions and twists and all those things that make languages difficult.

SCOTT:

Those 16 basic rules have remained largely unchanged. Nouns end in “o”, adjectives in “a”, adverbs in “e.” Which never changes so you can always recognize what part of speech a word is. The roots also never change.

- “Vero” (veer-o) is truth.

- “Vera” (veer-uh) is true.

- “Vere” (veer-ay) is truly.

So once you learn the root of a word, you can trust your intuition with unfamiliar words.

The same type of intuition that can’t be trusted with English, like when a child says they “ated” something, and we laugh at how adorably wrong they are for thinking they can rely on a nearly universal rule to express themselves…ha, kids…

For verbs in Esperanto, future tense ends in “-os”. For past tense the word ends with “-is”.

So “I will eat” is “Mi mangos”. Which means “I ate” is “Mi Mangis”. And they all share a root word so you can learn related concepts very quickly. Food, for example, is “mangajo”

The “open source” nature of Esperanto also means that it’s up to the community to help the language evolve with the times. Esther Schor is a poet and professor of English at Princeton University, and Esperanto speaker. From the TEDx stage in Rome, here she is explaining how this community-driven approach happens in practice.

ESTHER SCHOR:

They’ve had to be very resourceful about coming up with new words for a new times but that’s part of the fun and take a look the word for Internet in Esperanto is interreto. And notice that Esperanto hasn’t just swallowed the English word for “internet” whole. They’ve invented the word Esperantically for net which is “reto” inter”reto”. A cell phone or mobile phone in Esperanto is a poŝtelefono, or a pocket phone. And lertofono is literally a smartphone although I’ve heard on Esperantist refer to his as cromserbo “a spare brain”.

Becoming an Esperantist

ARIKA:

But the people who were attracted to Esperanto were less about the language itself and what the roots were, what the endings were, what the details of the language were, and the sort of Messianic message that Zamenhof was communicating with world peace. People latched on to that, and they had their first conference in 1905 international conference where they got to meet each other and get together and really get on board with the idea with the romantic and inspiring idea behind it. And that’s what then became the driving force of the growth of the language, not the language itself, or how good it was, or how elegant or, you know, easy to learn. It was, it was the mission behind it. That’s what really got people going on it.

SCOTT:

Esperanto took shape as a movement as much as a language, starting with Zamenhof. In fact, “Esperanto” means one who hopes, but it was originally not the name of the language. Zamenhof originally called it “An International Language,” and published it under the pseudonym “Dr. Esperanto.” He was The Hopeful Doctor. As his creation garnered more support, his followers started referring to the language as Esperanto…and there was no turning back.

Today true believers aren’t just Esperanto-speakers, they’re Esperantists. This is what drew Arika closer in.

ARIKA:

I think my dad had some books when I was growing up, and that I’ve flipped through. But I, there was a big story of someone who had devoted their life to this, but they actually got people on board. They actually had a fan club, and then people who started learning the language and using it, and I and I thought, huh, really, though, what do they do? Are they using it? I’m gonna go find out. So I went to some Esperanto meetings, conferences to see – “what are they really doing? And they were really doing something. And that was very interesting.

The Culture of Esperantoland

ARIKA:

There’s definitely a type like, you can totally roll your eyes and be like, Oh, my God, that’s so Esperantoland, and everybody knows what you’re talking about. And that means there’s a culture.

SCOTT:

Again, we’re only considering Esperanto a “failed idea” in the sense that it did not live up to its original lofty goal of…you know, total world peace. By the standard of invented languages, Esperanto is the golden goose – the “Ora Ansero” in Esperanto.

Today estimates put active Esperanto speakers between 10,000 and 2 million. It’s the only invented language with a population of native speakers. Around 2,000 people were raised speaking Esperanto as their mother tongue. Esperanto is spoken in at least 7 countries, there are Esperanto conferences every year, and as of 2018, you can even learn Esperanto on Duolingo.

How “Universal” is Esperanto?

SCOTT:

One of the chief criticisms of Esperanto as a “universal language” that borrowed from languages all over the world, is that in reality…it wasn’t.

It borrows from European languages. Mostly English, Spanish, French, Italian, German…

The syntax and grammar of Esperanto, like reading left to right, or the subject-verb-object sentence structure, most closely resemble Western European languages. It uses the same Latin Alphabet so it would be easy to recognize…if you spoke western European Languages.

So if you’re one of the billions of people living in places like China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam who DON’T speak a European language, Esperanto doesn’t feel very universal. So Zamenhof’s claim that anyone could learn Esperanto in a matter of hours is only close to holding up if you forget….roughly half the world’s population.

In The Land of Invented Languages, Arika Okrent writes: “This is a story of why language refuses to be cured and why it succeeds, not in spite of, but because of the very qualities that the language inventors wanted to engineer away. “

ARIKA:

Nobody sits down and writes out, here’s what French is, and now everybody learn it. They use it. And you know, eventually, yeah, you’d get grammar books and spelling books and things like that. But that’s not what made the language at all. But that always comes much, much, much later.

SCOTT:

Language is a natural and deeply human thing. Which means of course it’s flawed. But as Arika reminds us, those flaws aren’t really flaws at all. They’re the relics of history; evidence of something that was once useful, but isn’t any longer, like your appendix or wearing a tie.

ARIKA:

You know, that is what irregular verbs are. Why do we say you know, “I went” Instead of “I goed,” well, it’s leftover, it’s from this old previous part of the language.

The Art & Science of Invented Languages

SCOTT:

That embracing of illogical, seemingly flawed aspects of language also provides an interesting clue to understanding a different invented language:

Klingon, The language spoken by the fictional “Klingon” species in Star Trek. Klingon never aimed to solve the world’s problems, but has proven to be a lot “stickier” than most of the languages that did.

It was created for strictly artistic purposes, crafted by linguist Marc Okrand, building on early ideas from Star Trek producers, to bring the alien species and their culture to life. It was crafted to deliberately sound “alien” and is quite difficult to learn and speak, so true fluent speakers might be scarce, but the enthusiasm and community surrounding Klingon is extraordinary.

There are Klingon conferences held every year, where attendees are expected to speak only Klingon. You can learn Klingon on Duolingo. On Netflix, you can watch the series Star Trek: Discovery with Klingon subtitles. Theater companies in Chicago and Arlington, Virginia have even put on Klingon Versions of a Christmas Carol.

Which begs the obvious question “How do you say ‘bah humbug’ in Klingon? We did learn that Qapla means Success! And is a common way to end an interaction.

So what made a language designed to be brutal, hard to learn, and even violent sounding, more successful than those created to bring world peace and make misunderstandings a thing of the past?

ARIKA:

It had irregularities, it had dialect differences, it had really, really hard to pronounce sounds and really, really complicated grammar, it’s very difficult to learn. it doesn’t solve any of those problems about language. But people who really got into it decided, hey, let’s translate Hamlet into Klingon. And they did the whole thing into this, this really difficult language.

SCOTT:

Because that’s actually what language is. A language for a specific group of people with specific customs, flaws and traditions. As is true with any art form – acts of creative expression will always provide a necessary piece of the puzzle that is human nature. In this case, it’s simply what role language holds for us. When a language is crafted for artistic purposes, not linguistic ones, it seems we actually get a lot closer to what feels real, useful and human.

ARIKA:

No one’s out shopping for a better language. And you can’t sell a language with like a washing machine, this one has really great features…and this one’s a lot more logical than that one, this one has easier sentence structure than that one. People don’t look for languages that way. They’re like, Who are the people speaking that? Okay, that’s, this is why I need to get with them.

The Dangers of Any Universal Solution

SCOTT:

Other critics will fault Esperanto for it’s original premise: That differences in language are inherently a problem, and that a universal shared solution was the answer.

Pressure to learn any universal language, including English, can have harmful effects, particularly for minority or indigenous communities whose unique languages play such a critical role in their traditions, history and way of life.

More on this shortly as we dive into Endangered languages….

The Impulse of Language Creators

So it’s clear the impulse of invented languages prevails throughout history.

So for future generations, does Arika Okrent, linguist and tour guide of the invented language graveyard…does she think it’s best to ignore that impulse? Not exactly.

ARIKA:

But the point is not to cure language. It’s using natural language as your starting point as your inspiration. Like, wow, right? We did this really cool language and, you know, Siberia that does this really weird verb thing. I really like it. So I’m going to create a language that does that, too. But, what if we mixed it with, you know, Greek? And people do people follow their own vision for what they would like a language to look like, and they follow through and create it and then they take it to meetings to have other people look at it and critique it and appreciate it. That’s the new face of language inventing and it’s so much better for the inventors. There’s not years of toil and struggle and losing everything while you try to get the world to pay attention to you. There’s joy and fun and creativity.

You know, and some people would say, “it’s useless and why don’t why don’t you try, you know, saving an endangered language instead, and why are you doing this…” But it leads you to linguistics. Many kids that get into languages and end up doing, you know, revitalization of Hawaiian or something, they start with Tolkien and being interested in ‘how do you put words together with smaller pieces? And that can bring you to linguistics and other kinds of language activity.

SCOTT:

If you’re looking for a way to engage with the weirdness of language, and English in particular, Arika’s new book is a great place to start. It’s titled “Highly Irregular: Why Tough, Through and Dough Don’t Rhyme and other Oddities of the English Language.”

Chapter 1 is delightfully called “What the hell, English?” and tackles questions like “Why do we drive on a parkway and park on a driveway?” and “What is the deal with the word colonel?”

ARIKA:

…kids will ask you these questions, and you have no answer. My daughter asked me once, “why do we order a large drink and not a big one?”

And you stop and think okay, I’ll explain it. “You see, it’s, it’s it’s. I don’t know.” There’s no answer. But actually, there is an answer. And that’s what the book is.

SCOTT:

Go buy Highly Irregular and The Land of Invented Languages, there are so many more fascinating stories that we had to leave on the chopping block. Thank you Arika for your time and insight.

So to recap so far:

Ben Franklin probably still has enough energy to roll over in his grave every time someone explains what a “silent K” is to a 2nd grader. Language is a strange, natural, culture-shaping beast that refuses to be tamed…and the things that make our mother tongues unique are clues to follow, not flaws to fix.

Which brings us to Act 2…

How Can Endangered Languages Be Revitalized?

MAXX (PRODUCER):

Hi Everyone, Maxx here, I’m a producer for the show. I normally prefer to stay far from the microphone, but before we get into part 2 of the episode, I just wanted to add a quick note and a content warning, particularly for any listeners from indigenous communities.

The beginning of the segment features a recording of a highly respected elder of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation who has since passed away. As you’ll hear Scott explain, his name was Jerry Wolfe. In the recording, Jerry shares a few examples of Cherokee words and phrases and talks a bit about the role the Cherokee language plays in their community. So again, out of respect for the sensitivity around hearing from an elder leader who is no longer with us, the section featuring Jerry’s voice is about 2 and a half mins long if you’d prefer to skip ahead.

JERRY:

When you meet people there are several ways of greeting those people. One is ‘o-si-yo’ that’s the main one. That’s Hello. Or howdy, we all say ‘Howdy.’ Seo. (Cherokee), are you okay? Or you can say. (Cherokee) and that means the same thing. Are you all right?

That’s Jerry Wolfe, a highly respected elder of the Cherokee Nation in Western North Carolina. The recording of Jerry is from a video recorded in 2013 by Wikitongues. It’s one of thousands cataloged by the organization to help preserve and revitalize endangered languages around the world. Here’s Jerry explaining more about how the Cherokee Language works and why it’s so important to the Cherokee people.

JERRY:

Now the plurals are in the beginning of a word. However, we say in the very beginning of what we’re going to speak on, we can put the plural in the very beginning, the first character on ni, Ni, like a, nr, our ni, gel again. And that means the group, that’s the plural.

If we did not have a language, we would not be Cherokee people. But we are Cherokee people. And I’m very proud of that. Most of all the elders are gone, that spoke the language. They’re out of 14,000 members here Turkey, there are only less than 500, maybe even 400 Cherokee speaking people…some of the children learn it , but that were just about fading away.

SCOTT:

UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) tracks the state of languages around the world at risk of extinction. According to the most recently available data, there are an estimated 1,000 people left who still speak Jerry’s mother tongue. Unfortunately Jerry Wolfe passed away in 2018, bringing the Cherokee language a step closer to “fading away” as Jerry described.

MAXX (PRODUCER):

Hello – Maxx here again to clarify and highlight just a couple additional things that came to light as we were editing the episode. First, according to a 2019 ceensus, there are actually between 1500-2100 fluent Cherokee speakers today, more than the 1,000 estimated by UNESCO. There’s also remarkable work being done to increase that number – including robust learning communities within Cherokee Nation and growing early childhood immersion programs. There’s now a Cherokee Wikipedia site, they even became the first native tribe to use motion and facial capture technology to help preserve and promote the Cherokee Language. We’ll include links to all of the above at lookbothways.kinandcarta.com. So check it out to learn more. Okay back to the episode. Here’s Daniel:

DANIEL:

7000 languages are spoken and signed today, but 3000 languages could disappear in 80 years, marking the loss of half of humanity’s cultural, historical and ecological knowledge.

My name is Daniel Bögre Udell, I’m the co-founder and executive director of Wikitongues.

We spoke with Daniel to learn more about their work and why language revitalization is so important.

DANIEL:

So Wikitongues helps people keep their languages alive. We safeguard at risk languages, expand access to mother tongue resources, and we directly support language revitalization projects.

What’s Lost When a Language Dies?

Daniel and his team are working to build a massive bank of all the world’s languages by crowdsourcing audio files, lexicon documents and video oral histories like the one you just heard of Jerry Wolfe. Clearly no small feat. And it’s actually just part of what Wikitongues is currently working on. Because to Daniel and the growing number of language activists aiming to save endangered languages, language extinction isn’t just a loss of words.

STEPHANIE:

The consequence of losing a language for all of us is that we lose knowledge. Hey, everybody, my name is Stephanie Witkowski I’m the Executive Director of 7000 languages. 7000 languages is a nonprofit organization that works with indigenous communities around the world, to help them teach, learn and sustain their language through technology.

Stephanie and Daniel were gracious enough to be our guides for this portion of the episode.

STEPHANIE:

As a society, we lose knowledge and lose knowledge about what is possible, what languages are even capable of. And by that talking, you lose knowledge about what human cognition is capable of.

DANIEL:

One of my favorite facts and if there are any linguists listening to this, they might roll their eyes because I’m going to say something that’s a little reductive, but I think for like general purposes, it’s salient. There’s only about a couple 100 concepts that have a word in every language. And yet daily speech in every language is somewhere between like three to 5,000 words, and most languages have many, many, many more words than that. I think English gets 150,000 words. So the vast majority of vocabulary in any language is unique to that language. So when you lose a language, you lose all of these other things that the language encodes. And what are those things? One of the really big ones is knowledge of the natural environment in which the culture emerged, right?

So there are actually fields of science that fall under this umbrella of ethno-biology in which biologists and linguists work with speakers of different languages to unravel ecological or bio cultural knowledge of local plant and animal species that are encoded in that language to accelerate conservation efforts. Indeed, sometimes new species are actually identified by the scientific community that way, right? Because, you know, this culture has been here for centuries, if not millennia, and they and they know this ecosystem better than anybody.

SCOTT:

As Daniel mentioned, 3,000 languages are at risk of extinction over the next several decades. Organizations like Wikitongues and 7000 Languages are doing everything they can to prevent that from happening. Which often includes clearing up exactly how languages go extinct in the first place.

How Do Languages go Extinct?

STEPHANIE:

languages don’t necessarily die a natural cause of death

DANIEL:

I think one of the greatest misconceptions of the 21st century is that cultural diversity is waning as a side effect of globalization. When your average majority language speaker…So we’re talking about speakers of English, Spanish, French, Mandarin, Russian, right?… When they think of endangered languages or dying languages, they think…

STEPHANIE:

Oh, well, what’s the big deal about language loss, its natural languages evolve. We don’t speak the same English that we used to speak.

DANIEL:

Latin morphed into the romance languages we know today or that nobody in the English speaking world talks like Chaucer anymore. And while it’s absolutely true that languages develop and wax and wane over time as culture changes because languages are a dynamic reflection of culture, the current language extinction crisis is not a result of that phenomenon.

STEPHANIE:

those are two very different scenarios where languages are changing versus being exterminated… versus it being connected with human rights violations.

DANIEL:

…The current language extinction crisis is the result of policies that were ubiquitous until the 1970s and 80s.

SCOTT:

In the United States, it was legally mandatory until 1978 for indigenous children to go to boarding schools where they would be assigned English names, and often abused if found speaking their native tongue. Canada had a very similar system. In Mexico, it was legal until as late as 2003 to ban kids from speaking indigenous languages in public schools.

DANIEL:

You know, for context these are languages like Yucatec Mayan, Nawat, which is the official language of the Aztec empire, and so on. In Europe, similar policies took place well into the 1970s and 80s. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the predecessor to the European Union passed the charter for regional and minority languages, there was a quote by George Pompidou, the President of France in the 1970s. That kind of embodied the attitude of language policy in Europe, which was there could be no place for minority languages in a France destined to make its mark on Europe.

You don’t need to be a student of history or politics to see how language extinction is something that went hand in hand with colonialism and genocide and other kinds of recent and you know, some would say ongoing atrocities, pick any endangered language and look at the history of the people who speak it.

If you don’t have your language, you don’t really have access to your culture. And without your culture, there’s, you know, a certain kind of psychological and spiritual gap, or hole, right, that then can lead to, you know, destabilized communities and broken generational bonds.

Conversely, language revitalization actually fixes a lot of those things. So you know, in Australia, they recently in Arnhem Land, which is an indigenous majority region, started integrating language revitalization into core school curricula. And for the first time, graduation rates are above 50% There’s no, you know, nonprofit, you know, run by white English speakers that could have come in and fixed that graduation rate problem better than the actual integration of language revitalization into the program, you know, by the communities themselves. So there’s just, there’s so many reasons that it’s good for humanity, its, you know, its education, its economic developments. It’s scientific research. Its, you know, its cultural sovereignty. It’s a form of reparations.

Welcoming New Generations

SCOTT:

So what can be done? At 7000 Languages, Stephanie and her team are focused on the intersection of language education and technology. Through a partnership with language learning software company Transparent Language, they work directly with Indigenous, minority, and refugee communities to build custom language courses that anyone can use, at absolutely no cost.

STEPHANIE:

What our technology does really well is create courses for these users of the language. So we create vocab courses, we create grammar courses, conversation courses, it’s really a robust tool. So we work with communities to get their language data. And we funnel that into the transparent language tool. So that the output is that they have this really beautiful language course that they can use on their phones, that computer tablets, they can easily even use it offline.

SCOTT:

Whether it’s immersion-based Language Nests, classroom learning or even just through play, Stephanie says there’s no one path to language revitalization. What matters is getting children to try, make mistakes and feel excited about putting language to use.

STEPHANIE:

They are little sponges, children are meant to learn language, they’re born ready to do it. And you just speak to them, you just talk to them, you don’t have to tell them, oh, this is actually a past participle, right?

You know, it’s really community led and it has to be… Sometimes there’s an idea even linguists are really guilty of, saying ‘Well, language revitalization looks like this, looks like people sitting in a room and speaking in a language for one hour” Whatever, whatever idea it is. I’m of the mindset that all goals are good goals. ..So you know, even if a community says we just want our children to learn how to say, “hello,” we want our children to learn animal names, and we want our children to learn songs. Great. That’s language reclamation, that’s language revitalization.

Wikitongues at Work

SCOTT:

Daniel says he thinks about Wikitongues as spanning across three interlocking approaches that support language diversity. First is documentation: preserving a language through recorded speech, dictionaries and written texts. Next is revitalization, usually by reintroducing a language back into daily life and ensuring adults have what they need to pass it to a new generation.

The third is activism.

DANIEL:

Language activism is a little more nebulous, but it involves all the awareness raising and political action that could be part of creating an environment where language revitalization and documentation are more possible and accessible.

So we actually started just with documentation, we were crowdsourcing videos in as many languages as possible, ideally, every language in the world with all the caveats that come with a statement like that. And as we worked on that project, people started reaching out to us asking how do I save my language?

SCOTT:

History shows us that languages CAN be saved. Hebrew was virtually extinct as a natively spoken language around the second century. It was revitalized nearly 2000 years later in the 1800s and has since become an even more critical part of Jewish identity around the world. Daniel also shares the story of Donna Pierite.

DANIEL:

Donna Pierite is a member of the tunica Biloxi tribe of Louisiana, and she is the sole person who spearheaded the revitalization of their language in the 80s. And it originally had gone extinct in 1948. And the last speaker of the language worked with the linguist before he died to leave a dictionary behind. And so Donna would go to Baton Rouge and New Orleans and photocopy dictionaries and other old documentation books about the language and bring it home, she would teach her kids, then they started sending out newsletters about the process. And then they got other families involved. And today, 10% of the tribe is enrolled in immersion courses.

But you can imagine that that whole process, the original process was like, just go get the book about the language. And then the next thing was like, let me teach my kids. And then the next thing was, let’s get someone else involved. And then the next thing was, let’s get the tribal government involved. And you know, so the toolkit is really meant to help you walk through that whole process to think in terms of really project management in a funny ways, not unlike running an organization or a company or an activist project, right?

SCOTT:

The toolkit Daniel mentions is the Language Sustainability Toolkit, designed to create a roadmap for people seeking to revitalize a language at risk of extinction.

People like Windy Goodloe. Windy is a member of the black seminole community in Texas. Their language is called Afro Seminole Creole. Today there’s only 20 speakers left. With the goal of doubling that number, and armed with only the knowledge of those 20 people and a 1,000 word dictionary…Windy came to Wikitongues for help.

DANIEL:

And that’s and that was in the 70s or 80s I think and that’s all they have to to bring this language back. So Windy has been part of a cultural revitalization for Afro Seminole Creole, since the 2000, like early 2010s. And it started around the effort to save a cemetery in their community that were a lot of their community members were buried. They set up a museum, a small museum, and a nonprofit around that. And so language revitalization was kind of like the next step, right? Because in Wendy’s words, a cultural revitalization without the language like you know, how many, you know, events and t shirts, are we going to sell, right? Like, what do we do next? What carries us forward and on to the next generation?

So I’m really excited about is next year, we’re going to be opening this process up to public application, and we’re going to provide funding and training to 75 revitalization projects by 2025.

So if you’re listening and want to start a revitalization project, write us an email at hello@wikitonuges.org and we will let you know when the application process is open.

Technology & Inclusive Design

Whether it’s the robust learning software from 7000 Languages, the vast database of languages from Wikitongues, or even a recent app developed by Google called Woolaroo which uses AI to document and teach endangered languages, technology can clearly play an important role in solving the problem of language extinction and accessibility.

But… tech can also contribute to the problem itself….and sometimes in ways that many dominant language speakers would likely never even consider.

DANIEL:

Having access to media in your language and having access to core technology in your language is absolutely a form of linguistic privilege, right? There is research that would indicate that the inability to use your language on your device can accelerate language loss because there’s something subconscious that happens where if your phone is talking to you, and whatever the locally dominant languages it kind of sends a subtle message that your language isn’t important and that you shouldn’t really speak it anymore. If you want to be modern, if you want to be part of the global economy. So, you know, multilingual support is absolutely critical for inclusive design.

SCOTT:

One company that seems to be of the same mindset…Motorola Mobility. Back in May of 2021, Motorola announced that the latest version of the Android Operating system on Motorola phones would feature two indigenous Latin American languages: Kaingang and Nheengatu.

Kaingang is spoken by communities in Southern Brazil, and is classified by UNESCO as “definitely threatened” which means children no longer learn it as their first language. Nheengatu speakers are mostly found in the Amazon region, including parts of Colombia and Venezuela, and is considered “severely threatened” meaning it’s only spoken by about 6,000 people and primarily the older generations.

For Motorola, it’s part of a broader focus on accessible design and awareness about the role technology plays in language revitalization. To learn more about it all, we talked with Renata Altenfedler, Global Executive Director, Brand & Marketing at Motorola Mobility. Here’s my conversation with Renata:

Feature Interview: Renata Altenfelder

Scott Hermes:

Okay. We are joined today by Renata Altenfelder, Global Executive Director, Brand Marketing at Motorola Mobility. She is based in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and was part of a team that recently added support for two endangered languages to Android 11 running on Motorola phones, welcome to Look Both Ways Renata.

Renata Altenfelder:

Hello, how are you?

Scott Hermes:

I’m doing great. Thanks for joining us. So just to dive right into it, can you tell us about how the decision to include the endangered languages of Kiangang and Nheengatu? Hopefully that’s close on the pronunciation, how that decision to add those two languages into Motorola smartphones came about?

Renata Altenfelder:

we are always looking for ways to be disruptive to look at new technologies, and how to apply technology for the good. So how it comes to this program was the group of globalization and the group of languages that realize that there was a lack of a presence of indigenous endangered languages in the digital world. So they came with the project of saying, “what if we use our knowledge and our expertise in order to make those languages available into our smartphones?” So it it was well received. And then we got in contact with a professor, Professor viewmont vangelis. That is from unicam, one university, a big university in Latin America, and he works with endangered languages. And so looking at all of the endangered languages that exist today, we ended up choosing Kiangang and Nheengatu. Two, which are two very important languages in Latin America, not only in Brazil. And when we think about why we chose them, they are from the two biggest tribes of language we have in Latin America, there are the Marajoara, if I’m pronouncing it correctly, and the other one is the Tupi. So very important languages in our culture overall.

Scott Hermes:

And maybe just help us a little bit in were in Latin America or in Brazil, would you find native speakers of those languages?

Renata Altenfelder:

Yeah. So Kaingang in on the south, south east of Brazil, and then Nheengatu is in the Amazon area. So it’s also Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela.

Scott Hermes:

That’s great. And when you went to start working on this, obviously, you said you talked to a professor, but did you also work with the native speakers of those languages? And how did you find them? And how did that work out?

Renata Altenfelder:

One of the things that for us was crucial was to have to have credibility. And to have the truth behind this project, we need to work with the people who really talk and live that language in that culture. So a group of people that had people from the University, from Motorola from another partner that works with us on languages, they helped us to identify people at the Nheengatu and Kaingang communities to work with us. So we have native speakers working with us on the whole project. So they help us on doing the whole language in this whole vocabulary.

Scott Hermes:

And I think even in one of the languages like the dialects as well would vary, right? So how did you go about resolving some of those issues?

Renata Altenfelder:

I think is more than the dialect I think it would happen is they are two different languages. They have different expressions, the way that they refer to things are different, not only between them, but also among all of the other languages that we know. So at Motorola, we already supported over 80 different languages when we started this project, right, but this was a new one. So this group of people from the professor, the language experts from Motorola, and the people from the community together, they also had to work and identify the meaning of each one of the expression. It’s like we always say: there is this one word in Portuguese, “saudade”, then a lot of people know about it, which is about missing someone, but it’s a little bit more than missing. They also had their “saudade” words, and we need to explain what it is, and they need to explain what it is. And we found new expressions. And the opposite was also true. Like, because what is what is the importance of having those languages is that by having it, we are giving access to the people who are native to the whole digital universe, because they are able to communicate themselves with others, they are able to translate what they don’t understand into their own language. But also for those, like people who don’t know the language to know something different. So in order to do that, we also need to translate our own expressions to those two languages. Right? So it’s not just one way, it’s the both ways that we need to, to work here. So we’re learning from, from both sides, or three sides here.

Scott Hermes:

Yeah, for sure. If you have any good examples of say, I think it’s a great example of words that exist in one language, but don’t necessarily have a counterpart and others. So what coming from sort of the very highly technical world of computers and smartphones? I mean, is there anything stands out in your minds of a word that was difficult to translate back into either Kaingang or Nheengatu

Renata Altenfelder:

There was not specifically on the technical side, but inside of our phones, we do have some specificities, in terms of features. And one of them is what we call Moto actions. In Portuguese, or in English, the translation is very direct. On Nheengatu and Kaingang, and it was not like this, we need first of all, because Moto, and then action, so the way of talking about action is different, they don’t have the word for action. How to explain that. So there was a whole world of discussions about how to make it clear for them Because that is that those are expressions that they don’t use in their daily lives. They also didn’t know what it meant. So some of them were not used to using that in their daily life. So they needed to look at it in a different way. So that was, that was super interesting. So it’s all about as I was saying, I think it was learning from both sides on languages and also expressions, ways of working. So as you can imagine, some of them we’re not used to the timelines of a global company project. Especially on the technology side if you are locking a software version and if you miss the deadline, it means that whatever you are developing won’t be available on your phone when it’s launched. So we need to work very tight timelines, So also, there was something that we needed to find a way to combine those timings and make sure that this would work for both sides.

Scott Hermes:

Yeah, that’s interesting. I prefer if you figured out a way to make that sort of non deadline driven time apply to software development, that would have been a great breakthrough that I would have supported 100%.

Renata Altenfelder:

Agree. Yeah, but I think that is good, right? Like it’s really, really working on, what is this process of digitization, like how to work with different professionals from all across the globe? And there was a lot of different translations in this path, right? Because we are talking about not only we had Brazilian professionals, so the professor, the person who came up with this idea was a Brazilian guy. And then we had Juliana was the the manager who was leading this project on the globalization team. They were all Brazilians right. But the universal or the overall language that we expect, there’s a lot of on the English version, so that we had to translate from Nheengatu to Kaigang into into Portuguese for the conversation, but then we need to translate it into English, because a lot of the discussions on our side from the from the engineering part was happening in English.

Scott Hermes:

Wow, that’s, that’s a lot of work.

Renata Altenfelder:

That was a lot of work. But it was, he was so excited, we were like so much in love. And then we didn’t even thought about it. The other day, we count the number of words or expression, right, that the word translated or created somehow, for this, and that was over 500k. Wow, a lot of work, a lot of work. And so it’s, it’s, but it’s so much in line with what we believe, what I believe, which is really using technology to have a positive impact, right? This is not only about the language itself, it is about preserving your culture, right, your language is a very important part of the whole culture, because it does communicate and it does translate the way that that specific group of people think the way that that specific group of people act, right. So having this translated and having this into the digital world, which is where a lot of the things are most of the things that we have today, if not the total, almost the totality, are is guaranteeing somehow that this is have a continuity. And for me, this is super important. And and we need to make it like those languages at the base of the language that we speak today. A lot of the a lot of the words in Portuguese came from from languages like Nheengatu and Kaingang, so it’s, it is a way also for create and generate curiosity on the people to understand what is kinda and what is Ganga to write from younger generation, because they start, you know, seeing it on the news, they start seeing it on their own phones. We know young generations are always playing with their smartphones. And people are playing in so they see a different language there. When they look at they have a different language G on the keyboard from Google. What is this? So they start going after and trying to understand and this is a way of making the culture alive.

Scott Hermes:

I think that’s great. And preparing for this interview, we found a quote from a native ninja to Speaker we said, “Over time Nheengatu has been weakening more and more many times to discrimination on the language. People are ashamed to use it.” Do you feel like that by this action of including it more? So it’s now part of the you know, the future? Right, this is the present? Do you think that’s going to help with that?

Renata Altenfelder:

Yes, yes, I think and I really hope because what we know talking with them. And also talking with some people who study like indigenous languages across the globe, what is not happening is that young people feel ashamed because they think this is old. They think it doesn’t look cool. So you know, like, they don’t even talk with their grandparents sometimes on their own language. So having it on the smartphone, I think it’s the way also to show this, this youth that this is the language of today also, this is not a language that this is a language that they should be proud of using it, it carries much more than what they think. And I think also by having it classify as a language in this world also gives help other people also to break this barrier. We had an example of one of the guys who has been working with us on the expertise that made me sad when I heard and make me make sure that what we are doing is the right thing. He went to the city he lived in, in the in the Amazon, right so he went to the city code to look for a job. And then the guy asked how many languages did he speak? And he said two and then the guy said Okay, so to speak Portuguese, an English Portuguese in Spanish? And then he said, No, I speak Portuguese and Nheengatu and then the guy said, “Nheengatu is not a language.” That’s right. This is brought out this is this is this is killings how, like, you know, like this is this is killing everything in terms of culture, you know, like self confidence. So having itin places where people can look at and you know, you can pick up your phone and say look, how is it not a language? It is listed together with the other 80 languages in the world. And I have it here on the keyboard. So also, this was an important work that the team has done with Google. So all of the new androids, you will also be able to download it on your keyboard and type it in that language. So that’s what I’m saying – definitely this will help the languages to be accepted and to be known by a wider number of people.

Scott Hermes:

So now, the languages are embedded into a version of Android that runs on Motorola. What’s the what’s the broader plan for now that you have this mapping? Because I’m sure this is valuable to or useful in sort of many other situations. How does that information gets shared out for other versions of Android or just generally for use in the technical community?

Renata Altenfelder:

Yeah, so this is this is not for only for Motorola. So I think as I, as I said, the beginning our we started doing it. But since the beginning, we know this is bigger than one brand, right? Not only bigger than one all, I think this is bigger than any brand. This is about all of us. So this is an open source. And it is available on Windows 12 if I’m not mistaken.

Scott Hermes:

Windows 11 is the next one coming up.

Renata Altenfelder:

Yeah, it’s 11, I’m already on the next year. Already, it’s going to be available in all of muralla products, and on the G board, you already can download it.

Scott Hermes:

That’s great. That’s awesome.

Renata Altenfelder:

This is very important for us, right? Like this is not something that we want to be only for Motorola users. This is a part of who we are in our DNA that is really about disrupting the status quo and bringing technology that makes a difference in the lives of people.

Scott Hermes:

So obviously, this was a great success for you. Is there a plan to start on other languages? And if so, how do you decide which ones you might start on next?

Renata Altenfelder:

Yeah, we are now making studies across the globe. We don’t have the next one yet. But we are looking together with experts and professors to really understand what is the roadmap we keep working on that. It’s also really important to call out here that this is the decade of indigenous and dangerous language at UNESCO. So there’s also we believe that it’s going to bring attention to the topic. And we want to continue being part of this conversation.

Scott Hermes:

Okay, that’s great. Keep track of that and see see what’s so outside of language. What else are you doing, I mean, this is this is sort of very classic, inclusive, inclusivity and accessibility, what other kinds of things that are going on at Motorola that also make sure that Motorola continues to be both accessible and inclusive.

Renata Altenfelder:

A lot. So as soon as I was saying we had this pillar of inclusivity, in everything that we do, right, so I previously talked about Moto actions. And for me, that’s also one of the examples of how accessibility sometimes can be easy, but people don’t necessarily think about it. So when you when you look at the Motorola phones are some some tools there like the way that you can access your camera or your flash, just moving your hands and in, in a different movement, and then you can access the camera, the way that you can play with the size of the letters, the way that you can play with the colors of what you have in your phones.. On top of that, also, we had a lot of panels discussing what are the needs of the people in the future, and working together with the engineers to bring this to life into our products. So there’s a lot of things from the software execution from also like point of sale, we are developing furnitures, it’s really thinking about how people are going to enter we do have like stores and kiosks across Latin America and the globe. So how will people going to walk inside of our stores? What is the height of the furnitures that we have internally? How can they can grab the phone? So all of these are our thoughts, not only for one group of people, we’re thinking about different needs. So I think when we say that we have in our core inclusivity it’s important to say that it goes beyond the product itself. It’s in everything that we do.

Scott Hermes:

What do you think gets misunderstood about inclusivity? and inclusive and accessible design?

Renata Altenfelder:

When talking about inclusivity, in my view, it’s all about creating a new norm, right? People, we still have this concept that the majority is the law. And that the different groups don’t have the same rights. So I think by the moment that people understand that when you work with your minds, and you work with different people with different means, and you understand what they are looking for, and you start giving them this as a company, right? This actually is very positive for your results. Not only because people will look at you in different ways, but because you are going to access a different type of like different group that currently doesn’t have access to your products, because it doesn’t really solve their needs. There are people who think that doing something for a specific group or with a specific need is extra work, because it’s not worth it. And I can tell you, it’s worth it for different things, and not because it’s the right thing to do. But it’s also because this is going to bring you more money. So as a company, look at this as also a generator of results.

Scott Hermes:

Absolutely. So I mean, I think you just nailed it with this, that it’s the right thing to do. It’s the ethical thing to do. But then also you’re increasing your audience. So why wouldn’t you do that? Right? And so a lot of the things that make for good, accessible and inclusive design make for good design, right? So it’s not like they are two arbitrary things. It’s not a zero sum game. It’s not like, oh, if I make it accessible for more people that I’m making it worse for everyone, which is, you know, or worse for the majority, right? You can, you can do both, right, like I think we just demonstrated by, we have the ability to change languages on our phone, why not have as many languages as we can have time to get in there, just just do them, right? Like once it’s in there. And once everyone shares that, that translation base that you guys just started on, right, that’s just it’s easy to plug in now. So I think it’s just like, like you said, it’s, it’s trying to meet people where they are instead of expecting them to come to you, right? So you’re always gonna, it’s always the right thing to do. And it’s also a profitable thing to do. So I don’t see how you can not do it.

Renata Altenfelder

I think we have this statement aside when you are not excluding your excluding, right. And I think it’s exactly like this because when you are not looking at all of the totality of the needs, in your excluding the other one is like you have this block it, right? But when you are willing to open your mind and see you’re gonna see so many opportunities that you can jump in, and then you can do amazing things in that. Right. So I think that is for me the ultimate goal of all of us, we should have as humanity, right, like, stop putting people in boxes and just look at the good for everyone.

Scott Hermes

I can’t think of a better way to end our interview, Renata. But thanks for joining us, I really appreciate you spending the time and I really love to hear the work that you’re doing and the fact that I think it’s gonna mean a lot to the people who speak those languages and other people who are in the same community as the people who speak that language is to help better understand them and get curious about that language and start to want to learn more about that culture. So I think that’s also going to be another great effect of it.

Renata Altenfelder

Exactly. So and I thank you I thank you for the opportunity. It’s always good about like talking about that is always good about talking what we say like is technology with heart right? This is how can we humanize technology? How can we bring this up to everyone so very, very thankful for the opportunity.

Engaging With Indigenous Communities

Thank you to Renata for an excellent conversation. And thank you again to Stephanie and Daniel. To get involved and learn more about their work, visit wikitongues.org and 7000.org.

And if you’d like to simply learn more about the history and culture of indigenous people, we thought we’d leave you with some sage advice from Daniel.

DANIEL:

I think one really, really easy step that anybody can take is to learn about the original language of where you live. .. Maybe learn original place names. if you live in New York, learn that it is also the Navajo King, right? Learn about what was here, right and, and learn about what is still here, just in a, you know, in a state of political marginalization. More broadly, learn about what your languages were…the vast majority of us don’t speak the same language that our grandparents or great grandparents did.. So consider reclaiming one of your languages.

if everyone is involved in language revitalization, you know, their own personal language revitalization, that kind of normalizes it, for everybody else, right? And the more you normalize multilingualism, the more you make it easier for speakers of marginalized languages or at risk languages to use their languages, you know, everywhere, right?

That’s a wrap!

We hope you enjoyed our super-sized episode, or as you hopefulists out there would say, “Granda Epizodo.” If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our podcast on the podcastery of your choice. You can also follow us on Instagram at lookbothwayspodcast.

This episode was written and produced by Maxx Parcell with sound engineering from Chris Mitchell. Ear candy with light dusting of “humor” was provided by Scott Hermes. Original music composed and recorded by Ethan T. Parcell and Lucas Parcell.

If you have an idea for a podcast episode, visit lookbothways.kinandcarta.com and leave us a note, in English preferably, but if you wish, feel free to invent a new language and a new alphabet and leave us a note using it.