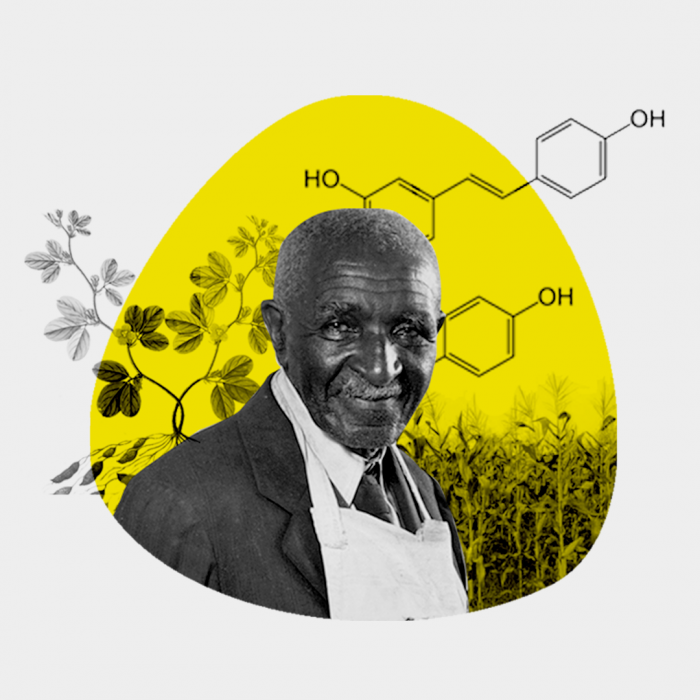

Is remembering George Washington Carver as “The Peanut Man” misunderstanding his legacy? Not only did most of Carver’s famed 300 uses for the peanut never make it beyond his “kitchen experiments,” but developing them as products was never his aim in the first place. With the help of Dr. Raymon Shange of Tuskegee University, we get to the root of why.

We then fast forward 100 years for an illuminating conversation with Emma Fuller from Corteva Agriscience about regenerative agriculture, the economics of sustainable change, and why Carver’s love for the “man furthest down” means not forgetting the farmers tasked with feeding the planet.

Episode Transcript

Schoolhouse Rock Clip: “I’m just a bill, yes I’m only a bill, sitting here on Capitol Hill“

Remember him? Of course you do. Do you remember any other part of the song? No it doesn’t start with “conjunction junction.” Different song, same genius of Schoolhouse Rock, circa 1973. Here’s the next verse:

(clip continues)

Unfortunately, young Bill the Bill on Capitol Hill is right. Statistically speaking, “dying in committee” would still make him luckier than most of his bill buddies. Because Congressional Committees are one of those things that sort of sound pointless but actually wield a tremendous amount of power. Like TikTok Dances, carbon dioxide, or the designated hitter.

In the US, there’s ONE Congressional Committee that’s often considered the most prestigious and most powerful:

The US House Ways and Means Committee. Why? In a word, money. Any legislation that’s tax, tariff or otherwise revenue-related starts in the US House Ways and Means Committee. It also has jurisdiction over small little programs you may have heard of like Social Security, Unemployment and Medicare….

It’s a big deal. So testifying there is a big deal. That’s why a century ago, in February 1921, it was national news that an African-American agricultural scientist by the name of George Washington Carver came to the still highly segregated Washington DC to testify before the committee.

At the time, US Peanut Farmers were being undercut by low prices on peanuts imported from China, and wanted Congress to pass a tariff. The United Peanut Grower’s Association asked Carver to speak as an expert witness. Carver was given 5 minutes to share findings from his experiments at the Tuskegee Institute (Now Tuskegee University).

Several members of the committee refused to take Carver seriously. Some even thought blatant racism provided the most effective line of questioning. One Congressman asked Carver if he would like some watermelon to go with his peanuts. Carver, who was born into slavery in 1864, refused to be rattled, instead replying that he thought watermelon was fine, but as a dessert food it doesn’t compare with the pies, cakes and cookies he could make with the peanut.

Soon Carver’s 5 minutes were up. But the committee wanted to hear more.

He explained that the combination of peanuts and sweet potatoes can provide a complete, balanced diet. He shared recipes for peanut bread, peanut sausage, peanut ice cream, peanut coffee, but that food was still just the beginning…

Again Carver’s time ran out. And again it was extended. Carver talked about peanut-based gasoline, peanut shampoo, peanut soaps and peanut face creams. He talked about how natural paints could be made from soybeans, glue from sweet potatoes, and how the economic impact of it all could transform the lives of American farmers.

Is Carver’s Legacy Often Misunderstood?

Carver’s enthralling testimony put him and his self-proclaimed 300 uses for the peanut on the map as “The Peanut Man.” Carver referred to his inventions as his “kitchen experiments”. Several of them WERE successfully brought to market. But most were never fully realized, and some flat out didn’t work as designed. But it never slowed him down. Carver developed hundreds of practical uses for crops that had largely been ignored by farmers, yet only filed for a few patents over the course of his career, and repeatedly turned down lucrative offers to leave his beloved Tuskegee Institute.

So why go through all that trouble? Why the 300 uses…why the impassioned plea to Congress about the products to be made with his crops, if he wasn’t all that concerned with the process of actually making them? Why was Carver seemingly more interested in GROWING the peanut market, than trying to corner it himself?

Hello everyone, I’m Scott Hermes, welcome to Look Both Ways – a podcast about experimentation, world-changing ideas, and the willingness to get things wrong.

The show is made possible by Kin + Carta, a digital transformation consultancy who exists to build a world that works better for everyone.

Each episode of Look Both Ways follows a two act structure: First, the unsung experiments of history…the ideas, attempts and prototypes often overlooked in favor of their more famous and successful siblings.

Act 2 then zips back to the present day to put the spotlight on exceptional people working to solve complicated problems. Often the same types of problems our heroes in Act 1 were working on.

Today, we’re talking about Sustainable Agriculture. What it actually means, why it’s so very necessary, and a conversation with Emma Fuller, Science Lead for Carbon and Ecosystems Science at Corteva Agriscience, about how to make it happen at the scale necessary to overcome the very real dangers of climate change.

But first: back to peanut shampoo.

George Washington Carver’s Land Ethic

Ask people what they remember learning about George Washington Carver, and the same answer will come up again and again:

(clips of “The Peanut Man” and “Didn’t he invent peanut butter?)

Of the many concoctions credited to Carver, peanut butter actually isn’t one of them. But he did cover just about every category of consumer product you could think of, many beyond just peanuts. His inventions also included sweet potato rubbers and inks, Soybean cheeses and baking flours, wood stains from clay, concrete reinforcements from wood shavings, and road paving surfaces from cotton stalks.

Sounds like a budding capitalist right? So was that Carver’s plan? To introduce the world to a plethora of new exciting products and sell Carver Peanuts & Legumes LLC to Kellogg’s for millions? Not exactly.

George Washington Carver’s obsession with peanuts, soybeans and sweet potatoes wasn’t for the sake of his wallet. It was for the sake of farmers and the land they tended. More specifically, for the soil.

The Post-Civil War American South was still dominated by the farming of cotton. Cotton sucks out important nutrients like nitrogen from the soil. So when cotton is the only crop farmed on a piece of land, that nitrogen never gets put back, and the soil suffers… which means yields suffer, and farmers suffer….and in particular black sharecroppers suffer, often falling deeper in debt to their landlords. A devastating domino effect that starts with a lack of nitrogen.

Growing crops like peanuts puts that nitrogen back in the soil. By alternating between growing the two, cotton yields would remain strong, the soil would stay balanced, and farmers could harvest peanuts by the bushel.

But what to do with them?

Carver had a few ideas. 300 to be exact.

Growing the Peanut Market

Carver knew that smarter choices and greater crop diversity could help lift southern farmers out of poverty. Developing an abundance of uses for those crops set up the same type of economic incentive that made cotton farming so lucrative.

Today we call the practice crop rotation. As a principle, it dates back to ancient civilizations. But before Carver, conservation-minded farming methods were effectively unheard of, particularly in the cotton fields of the American South.

DR. RAYMON SHANGE:

I think at least in some schools of thought people would call it a land ethic.

My name is Raymon Shange. I am currently the Associate Dean for cooperative extension on the college agriculture and environment Nutrition Sciences at Tuskegee University, and also serve as Director of the Carver integrated Sustainability Center here at Tuskegee University.

SCOTT:

We talked with Dr. Shange about the driving force behind Carver’s “kitchen experiments.”

DR. RAYMON SHANGE:

The inventions and uses for these different plants was almost, I will call an accident of his, of his ethic. I think you could force that many inventions out of a plant nowadays, but it will probably take you an entire team of researchers to do but I think it goes to show when the scientist or an academic has a certain powerful perspective, such as land ethic that it could really inform their perspective a lot more you know, then I’m here to actually rip apart this peanut and make money or profit off of it you know.

SCOTT:

The object of Carver’s focus is the same thing at the heart of the regenerative agriculture movement today: The soil. Here’s what Dr. Shange had to say:

DR. RAYMON SHANGE:

Because I mean, it’s the most important thing. I mean, when we see the degradation of soil can degrade civilization, right? I mean, that’s what our entire food system is based off of. some of us in the field, see soil as the digestive system of the planet.

we’re actually rediscovering now is that diversity is the key to soil health., I mean, imagine if you ate one, if you ate one particular thing for your entire life. You know, that’s not going to promote good microbial gut health. And that’s the same thing with soil health.

And some of those practices came through in the teachings of Dr. Carver who promoted using composting animal waste in that organic matter, and adding it to soils. And there’s actually a bulletin, where he talks about maintaining the version for fertility of soils.

this is the microbial world, you know, we sometimes center ourselves in it….in terms of what keeps the planet systems functioning, microbes are the key to the planet.

SCOTT:

Carver aimed at the mindset of farmers, one hungry skeptic at a time. When he was teaching and working at Tuskegee Institute, he put his classroom on wheels. Carver called it The Jesup Agricultural Wagon – named after Moris Jesup, a New York banker and philanthropist who financed the project.

Carver would load up the Jesup Wagon with peanuts, soybeans, sweet potatoes, pecans and other legumes, and talk with farmers about how growing new crops could transform their soil. Some even credit Carver’s Jesup Wagon as the first ever food truck. So yes, the next time your day is rescued by a well-timed Empanada truck…you know who to thank.

Carver taught at Tuskegee for 47 years, focusing on crop rotation methods, developing cash crop alternatives, and helping new generations of African-American farmers learn how to farm self-sufficiently. Dr. Shange says the key to understanding Carver’s impact, at and beyond Tuskegee, is to take as wide a view of his life as possible.

Understanding the Whole of Dr. Carver

DR. RAYMON SHANGE:

When we take account of him as a total human being, and the things that he actually contributed to, for all humankind, we saw that he was a spiritualist. He was a scientist, a humanitarian, a healer, engineer, a teacher, a mentor, an inventor, and so much more. When we accept this whole being approach, we see how how magnanimous of a man that Dr. Carver was.

SCOTT:

Carver’s closest attempts at turning his work into a thriving enterprise only bring his humanitarian side further into focus. For example, he started the Carver Penol Company, which sold a peanut based-medicine to treat diseases like tuberculosis. Carver’s hopes were high, but sales never took off and the FDA eventually deemed it ineffective.

He also developed a peanut-based massage oil, believing it could help treat infantile paralysis, aka Polio. While it was thought to work initially, researchers eventually determined it was the massage, not the peanut oil that was helping restore some mobility to paralyzed limbs.

Experimentation has always lived at the heart of agriculture. In his work, Carver helped farmers and students learn to even further embrace the principles of good scientific thinking and the trial and error that comes with it. There are not many audio recordings of Carver speaking, but here he is; speaking about his “kitchen experiments”, courtesy of Iowa Public Radio:

The laboratory is simply a place where we tear things to pieces. Sometimes we can get them together again if we want to put them together, and sometimes we can’t. But nevertheless we can tear things to pieces and get to the truth that we’re searching for.

The New Generation of Leaders in Agriculture

Thomas Edison once offered Carver a $100,000 a year salary to work in his labs, which Carver declined, staying with Tuskegee and his $1,000 a year salary. When Carver died, he even donated his entire life savings of $60,000 to the Tuskegee Institute to ensure they could continue the work…..of tearing things to pieces and getting to the truth.

Today Dr. Shange, his colleagues, and the students of Tuskegee University are doing exactly that. As the Director of the Carver Integrative Sustainability Center, Dr. Shange leads a group of faculty and students focused on finding new ways to enhance the profitability and sustainability of small, historically disadvantaged, and underserved farmers, ranchers, and rural communities.

DR. RAYMON SHANGE:

We are a very young sustainability center. We are kind of a ragtag group of people that have the same are we want to have the same ethic and work with the same ethic as Dr. Carver, Earth first and then humans, and just try to do our best wherever we land. We try to utilize appropriate technology. And we do probably a majority of our work is outreach, we do some applied research in the field as well. We’re still young, still growing. But if you just go to tuskegee.edu and look up CISC, we’ll pop up. We also actually do have a magazine as well that’s free for distribution. And if it’s not currently on the site, you can actually reach out to me at rshange@tuskegee.edu

SCOTT:

We’ll include links to all of the above on our website at lookbothways.kinandcarta.com.

Dr. Shange started his PhD program at Tuskegee in 2006. He says he’s somewhat shocked but absolutely delighted that conversations about microbial ecosystems and soil health are making their way into the mainstream. He said he hopes people continue being curious about not just HOW their food is made but by who is making it.

DR. SHANGE:

You know, it being in the space where people are kind of just buying without thinking about what they’re buying, whatever it be, puts us in a dangerous situation. But the fact that I’m running into more and more people that understand more about the food system is very encouraging.

What else makes me encouraged is to see people thinking more about how to support black, brown indigenous farmers. To me, there’s always kind of been, there’s always been a little bit of hush around the conversation. But I think it’s been brought to the at least a national forefront in the past two years. We’ve seen first of all, we’ve seen a great decrease in small farmers regardless of their race. But then, to look in specifically black and brown farmers, has been an even greater decrease. So seeing people actually asking questions about that as well, and seeing young people of color that are getting into farming is very encouraging.

The Man Furthest Down

When welcoming new students to Tuskegee, Dr. Shange says he often relies on one of his favorite quotes from Carver. The quote reads:

“The primary idea of my work is to help the ‘man furthest down‘, this is why I have made every process just as simply as I could to put it within his reach. How far you go in life depends on your being tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving, and tolerant of the weak and the strong. Because someday in life you will have been all of these.”

DR. SHANGE:

it’s a statement of, of his ethics, but even more so, a statement of his humility, and dedication. We talked about some of the some of the Dr. Carver’s accomplishments and just The legend himself someone with all of this imbued with all this talent and genius that will say you know he was offered a job at Ames college was was would become Iowa State but he turned that down to come to Tuskegee Institute and stayed his entire career to me that’s the that makes a huge statement someone that be someone that talented can make that choice you know who am I then to not lend you know my small talents to continue in that I mean if we don’t care about the person furthest down who do we really care about then?

Growing Enthusiasm

Modern agriculture is relatively unmatched in the scale, complexity and urgency at which sustainable solutions are needed. Dr. Shange says it’s daunting, but that he’s encouraged by a resource that’s historically been somewhat scarce:

DR. SHANGE:

I’ve got a lot of colleagues at other universities too, that work in ag. And the, the, the excitement of young people right now around farming, food. Just agriculture in general, is, is empowering and makes me love to go to work every day. So it may be a different future, it may look different. I mean, because this next generation is very much into the technology, technologies that will make farming easier. But at the same time, to see that there’s more people interested, especially at the small scale, I think is a wonderful thing for the country, as well as the world yeah.

SCOTT:

Huge thank you to Dr. Raymon Shange, for taking the time to speak with us.

George Washington Carver has become the type of American folk hero whose legacy is sometimes simplified down to what can fit on a bumper sticker. But pinning him as “The Peanut Man” tends to overlook what he valued most in favor of a “food-inventor” type identity that could be just a couple steps away from the Orville Redenbachers or Oscar Meyers of the world.

Like Dr. Shange said, Carver’s many uses for the peanut were an accident of his ethic. Understand the soil, understand the earth’s natural processes and work within them, not against them….

George Washington Carver was preaching sustainable agriculture over 100 years ago. And he was simply continuing what indigenous tribes and other ancient civilizations had been practicing for hundreds of years.

Today, no surprise, a great deal of modern agriculture does NOT follow these sorts of practices. And it costs a lot to feed the planet: in the US today, greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture account for about 10% of total emissions. Specific practices known as regenerative agriculture present an extraordinary opportunity to not only emit less, but actually SUCK carbon OUT of the atmosphere and store it safely in the ground. Unfortunately, in the overall landscape those types of practices are still a small fraction of what agriculture looks like around the world.

So how do we close that gap? How do we feed the planet AND avoid climate disasters? In Part 2, we talk with someone working hard to answer those questions.

Part 2: The Road to Sustainable Farming

In Act 2 of today’s episode: A deep dive with Emma Fuller, The Science Lead for the Carbon and Ecosystem Services Portfolio at Corteva Agriscience. You’ll hear Emma talk about what regenerative agriculture and sustainable farming look like in practice. She’ll talk about things such as cover crops, crop rotation, and no-till planting vs full-till planting.

In the agricultural world, pesticides, herbicides and synthetic fertilizers fall into a broad category of “inputs”, and selling inputs is one part of Corteva’s business. You’ll hear from Emma that there are important nuances worth understanding about how those types of inputs are used, and why it’s not always as black and white as we may want it to be.

Second, like most businesses in the world, Corteva knows it’s critical to become as environmentally sustainable as possible. They’re working towards very ambitious goals to achieve by 2030, including reducing on-farm emissions by 20% while strengthening yields for farmers; and training 25 million growers on soil health, nutrient and water stewardship, and biodiversity conservation.

The short of it: Creating environmentally sustainable ways at scale that keep up with the demands of a rising global population is, well, complicated. Emma is someone taking a fascinating hands-on approach to getting the science, economics and daily farming operations to all work in harmony. So we’re thrilled to get to chat with her.

A couple other terms to know:

Indigo and Nori. These are both carbon marketplaces. A carbon marketplace is where carbon credits can be bought and sold. So people or businesses looking to lower their carbon footprint, for either ethical or legal reasons, can use companies like Indigo and Nori to buy carbon credits from farmers who are using regenerative methods to pull carbon out of the air. Emma is also a big believer in the critical role marketplaces like Indigo and Nori can play in making large-scale sustainable agriculture possible.

I also just want to add that I do have some experience working in the Agriculture sector, including work with Corteva, although not with Emma. So please excuse the nerdery and excitement you’re about to hear.

Okay with bases covered,

We are joined today by Emma Fuller, Science Lead for Carbon and Ecosystem Services at Corteva Agriscience. Hi, Emma, welcome to the show.

SCOTT:

We are joined today by Emma Fuller, Science Lead for Carbon and Ecosystem Services at Corteva Agriscience. Hi, Emma, welcome to the show.

EMMA:

Glad to be here.

SCOTT:

For people who don’t really know corteva, would you mind explaining a little bit about what corteva does, and then talk a little bit about your role at the company?

EMMA:

Yeah, Corteva sells inputs and tools to farms. So those fall into three big categories. One is seed, corn, soy, alfalfa, those sorts of big broad acre row crops, types of seeds, and then also what we call crop protection. So it would be herbicides and pesticides to help support those crops production and control weeds and pests. The third business platform that we have is digital software. And that’s where I live. And so that’s a broad suite of agronomic and profitability focused tools to help farms run their operation and manage their business and understand profitability. What I do in my day job is I am the Director of Sustainability Science. I really focus on where and how our software can make a difference in accelerating and solving some of the unique challenges that we have with agriculture, and especially on the environmental side of the house.

SCOTT:

So first off, sustainability can mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people. So it for your job and for what you can affect at Corteva? How do you define sustainability?

EMMA:

Yeah, I’m really pleased that that’s the frame that we’re starting with because I have this terrible love-hate relationship with the word sustainability. it’s not a useful term because you have to say, Okay, well, what do you actually mean by that? So specifically, when I think about sustainability, I am mostly focused right now on environmental sustainability. … it’s primarily issues around water quality, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity – those are general themes that come up again, and again, soil health, those sorts of interconnected issues of what’s happening with the land, the water, and then the crops, that you’re not growing up the animals that you’re not raising what’s happening with them.

EMMA:

the issue is, is not been with the science, right? It’s not been with the tech, it’s been with the value proposition both upstream and downstream to farmers, right? Like there was just not a lot that value farmers are going to get. So that’s been the sort of focus of my work at a really global scale is where is there enough persistent value for farms to make it worth their time to enter in all the sustainability data? Or how do we make the capture of that data cheap enough to reduce that side of the cost benefit equation?

So in the last couple of years, carbon markets have really exploded, and so a lot of my attention has been focused there. And I started kicking the tires of that in 2019, with our like, very early, what I would call alpha with nori, and one of our customers Trey Hill, and sort of hack that together, Trey and I and the head of product of nori put that together to sort of test that value prop. And so that’s been, you know, we can talk more, but I’ve been somewhat bullish despite a highly uncertain area and a very new space.

Understanding Carbon & Farming

SCOTT:

So explain how farmers fit into carbon markets and carbon credits.

EMMA:

There are many different ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and sequester carbon. Some of them are engineered by like climeworks, and other sort of direct air capture buried in the ground sort of stuff. And then there’s also what we call nature based solutions. So these are ways to cultivate our landscapes and our oceans in ways that can accelerate the amount of carbon sequestered and reduce the amount that’s emitted. Soil is one of those huge opportunities in the nature based climate solution space, basically, farms can increase the amount of biomass, they grow, the amount of carbon goes into the soil and reduce the amount that’s decomposed that’s lost out through respiration. And through that net, increase the amount of carbon are pulling out of the atmosphere relative to that, what’s returning to it in the cropping cycle. There is a ton of landmass devoted especially to row crops. In the US, it’s like 280 million acres, right, just a tremendous base. And what’s really exciting about farming is that much of this, I would say, pretty much all of the practices we’re talking about right now, don’t cause yield impacts. So there’s not a concern of competition. So it’s like you get both your ecosystem service of production of food alongside an increase in ecosystem services of carbon sequestration. So it’s this win-win and the technology is present today. So this is not depending on an innovation cycle, right? Where in five years, it’s going to be scalable and cost effective. These are practices that farms have been doing for centuries at this point, like this is not new. And it’s crazy. When you look back into like the 1800s. They were talking about the same things. So that’s what’s profoundly exciting about it, although that underscores the challenge. Like if we’ve known about it for so long, why aren’t we doing it? But I think that’s what’s really exciting about this is this is one of the many tools we will need an toolkit to be able to address insect make a dent in climate emissions.

What does business as usual look like?

SCOTT:

Awesome. So maybe walk us through one of those things of like, if I if I, again, because most people on our audience are not farmers, you know, so the if I grow, let’s just take corn as an example, because that’s, that’s a pretty common one, I would think, or, you know, work or soy, but you know, sort of like what would be a way that I would normally farm it or, you know, and what would be the way that farm that wouldn’t be helpful for carbon capture, and then what are the changes I would make, to be more to capture more carbon?

EMMA:

Yeah, so in the business as usual sort of scenario for farming, corn has often been what we call fuller conventional till. So really turning over the soil, the top of the soil completely to flip and bury the crop to prepare the seedbed, so that it’s a fresh bare soil landscape in which you’re sort of planting seeds. You think of that sort of typical stock photograph of the seedling or whatever, and that soil is clean and brown, and there’s nothing in it except for that little seedling. That’s what sort of baseline business as usual, sort of full till conventional tail might look like, that’s, you know, can be achieved through a variety of ways. But if you also think about the stereotypical farmer with a plow, often behind a horse, they’re using a moldboard plow, which will flip that. Small side note: my husband and I have a small farm, use draught animals and for our power, talking old school stuff. And we plowed so we can talk about that to the fact that I work hard to address that, but I do it at home. So there’s lots of complexity here. And so that would be the sort of full till. The other way that you’d often do it is say, you plant your cash crop through the growing season, and then you harvest it, and at the end, you’re done. You leave your field fallow for the winter, right, because you don’t want to spend more money on planting more crops or whatever. And so everything’s sort of, especially in temperate, northern latitude, where things get cold enough that it won’t grow, you don’t need to do anything for that ground. That’s conventional.

The regenerative flipside that sequesters carbon is no till, completely getting rid of the till. So leaving that soil intact, adding a cover crop over winter; adding more crops to the cycle, so that you’re having something growing in the fall before winter hits, and then again in the spring before you terminate to start your cash crops, you have more biomass. And then also adding a diversity of crops. So starting to add alfalfa into the rotation or legumes, beans into the rotation, and then possibly including livestock, so helping them graze down your cover crop, adding more organic amendments, like manure into your system. Those are all examples of quote unquote, when people are talking about regenerative AG, those are the practices.

SCOTT:

It’s me, future Scott. Just jumping in to give past Scott a break.

Regenerative agriculture has incredible upside. The practices Emma just described: no-till planting, using cover crops and animal grazing rather than artificial fertilizers, using a diverse set of crops to balance the soil like George Washington Carver taught us…the superpower these practices unlock is the ability to sequester carbon out of the air and store it in the soil. And as carbon emissions continue to trap heat and warm the planet, the ability to not just cut emissions but actually take it OUT of the atmosphere will be a vital tool in fighting climate change.

According to the Columbia Climate School, the Earth’s soil could actually store as many as 4,000 Gigatons of carbon. Even the 2,500 gigatons stored in the soil already is about three times the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, and four times the amount stored in all living plants and animals. So it’s an extraordinary weapon in fighting climate change, and it all starts with farmers.

So we asked Emma: what’s holding us back?

The Economic Challenges to Regenerative Agriculture

Complexity. So regenerative AG is a more complex set of operations. you’re juggling many more species, you’re juggling, you’re trying to cultivate the natural system to take on a lot of the synthetic inputs you were doing yourself. So you’re trying to increase nitrogen capture from your late your, your legume cover crop, right? Rather than putting in synthetic nitrogen yourself, right. So you’re starting to try to like, build up the resilience of your soil to take off some of the help that you had to provide as a farmer. But the nice thing about being, you know, putting that in is you can measure really precisely exactly how much you put down. It’s much harder to estimate how much nitrogen your cover crop took in, and exactly what the microbes are doing with it.

It takes a lot of experimentation to figure out what’s the right mix of cover crops, how to do the you know, increase residue, like when you don’t go to no till you’re not incorporating the crop biomass, you don’t harvest back into the soil? How do you manage that, how you might get new pests, potentially new weeds that come on the scene. So all of that it’s complex.

The benefits, like we said, accrue over time, right, like five years, seven years, you know, sometimes you see the festive three, but it’s overtime long term. And the magnitude is really hard to predict, like, I can’t tell our customers. Yeah, in three years, you’ll see a, you know, 25% reduction in nitrogen, like you might see a 7% reduction in seven years. <ost of these farms are operating with very slim margins. You know, they’re not able to take that necessarily, despite whatever they may want to do that really a lot of times operating year to year in terms of making investment and management decisions on the margin. So it’s hard to say spend a bunch of time and energy and possibly startup capital to buy new equipment, buy new inputs, those costs are concrete and their immediate for these diffuse long term benefits. So that’s what’s really hard.

How Carbon Markets Can Accelerate Change

What carbon markets do in that landscape of challenges is they provide more concrete value up front. They say, there is a value here to carbon sequestration. There’s a value here to reduction in greenhouse gas and we can pay for that. We can start paying you for that in year one. That also ramps over time, right? You get bigger benefits the longer you go in carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas reductions, the longer that you do these practices, but there is another value. So I would say that today, with price carbon prices where they are, carbon markets alone do not pay for these practice changes, but they can help accelerate these practice changes, they can help de-risk of these practice changes.

So that of a farm is already considering this on some of their acres to address some of the other agronomic issues they have, whether it’s erosion, or pest pressure, which these practices can help with, here’s one more reason to help you say do it this year, don’t do it next year, do 100 acres, don’t do 20 acres, this is the year to do it.

Farmers Adopting Technology

SCOTT:

So I, we talked a little bit on this, and we’ve touched on, you know, we have these technologies. But sometimes it’s difficult to get farmers to adopt them. And again, you you just laid out a great case. Why Right? Like is it financially viable? Is this going to be successful? Right? Is it worth the investment? Right? So how do you go about that? I mean, like, how have you approached that problem in terms of farmers who are even, you know, again, using not advanced technologies here? You know, how is the how’s that happened for you, or anybody at Corteva, to try to get people to adopt technology?

EMMA:

most of our successes have come from listening to farmers themselves, right? Them telling us what they need and what they want. And I think one of the things I love about working at granular and corteva is that we are listening to our customers every day, we have the ability and access to those farms to say, tell me why this isn’t working for you? What’s the barrier here that you’re facing? Or what’s the cost that you’re trying to reduce? I think often people fall into that trap of trying to improve the returns on the land without thinking about the increasing cost to labor. So you have a new irrigation tool that helps improve your water efficiency, right. So per acre, you’re seeing an increase in yield relative to the amount of water that you’re using. But it’s a new tool that’s complicated to use. And like, you know, if you train a new guy on it, and stuff like that, and they don’t have the time for that, or the appetite for that, and the returns per acre are not enough to be worth it in their mind. So I think that’s sort of the structural challenge that I think everyone in ag tech falls into, at one point or another in their lives is like, yes, this net, like makes another dollar per acre and I’m doing it like, I don’t care. I don’t have the time.

SCOTT:

I think you mentioned that your original background is not in farming, but you’re now into farming. So what would you know? And then obviously, you’re you get to go out and meet farmers as part of your day job. What was like the sort of the biggest epiphany that you had, or one of the biggest, you know, early on discoveries about farming that, you know, sort of shattered some misconceptions.

EMMA:

This was like a real surprise to me coming into farming in the agricultural space as a data scientist at granular just, you know, we run at home a very typical family farm in like the public eye, right? Like we have about 15 acres, we do a farm stand, we do a CSA, like we do that sort of scale, farmers market fare, direct to restaurants, direct to customers sort of thing. When you look at our customers in Granular and Corteva, they are also family farms, but they are running thousands of acres. Right. And it’s crazy for guys on this operation that run 5000 acres and you walk out and it’s planted perfectly and precisely. And all of that has been because labor is so expensive. And so what’s hard about regenerative Ag is that it just makes it more complex to manage, you need more people that are more skilled and have the time and bandwidth to be able to, to do that. And the acre base that you need to do it on. It’s so big that that it gets it gets hard really fast.

How We Got Here

SCOTT:

Hey it’s me, future Scott again. What I really appreciated about Emma’s perspective in helping us understand these challenges was that she actually kept reinforcing what George Washington Carver became famous for saying: Caring for the man furthest down. In this case, the farmer. It’s easy to retweet something snappy about agriculture destroying the planet in between bites of a PB&J whose ingredients came from 4 different countries and traveled thousands of miles to get to my kitchen cabinet.

It’s much more difficult to be a farmer, whose livelihood depends on an unpredictable crop yield, being tasked with both adjusting to the realities of climate change, AND transforming their way of life as quickly as possible.

Which was about the part in the conversation I kept asking myself, how did we get here?

The short answer to that question is the same answer to why Carver created hundreds of ways to use the peanut. Incentives.

EMMA:

The reason that we have a cropping system, a food system, the way that we have today is because we have paid exclusively for yield. Right? That’s all all we pay for. Right? Like a farm’s profitability is directly tied to the amount of grain they can grow per acre. They are not, they are not, they don’t field the costs of water quality downstream. They don’t field the costs of water scarcity until like, literally, there’s no water left, right? All of these things are priced outside of that, both for good and for bad. They also don’t get any value out of the services they do in terms of water filtration, or greenhouse carbon sequestration, right? So there’s no value in it to them to invest in. …what’s exciting, you know, in our, our partnerships with Nohrian, with Indigo now is starting to see these corporate, business-focused machines starting to now optimize on something more than just yield, right? So starting to say, how do we scale this commercially, because commercially, this is now a priority. This is not just, it is also a sustainability, societal priority for us as a company, to you know, do the right thing. But it’s also now a commercial focus for us. And that just fits right into the way that capitalism works. And so we’re trying to make change in the system today, not talking about capitalism, which would be another fun conversation. But yeah, what’s Yeah, like, if we’re gonna make change in today, in the next five years, just sort of my timeframe for thinking about these solutions. We need everything about what’s going to happen in the next five years, we need what’s gonna happen in the next 10 years when you think about what’s gonna happen, the next 30. But I think one of the roles that we can play, especially in a big company, like Corteva, is how do we accelerate change in the next five.

The Data Challenge

SCOTT:

Yeah, that’s absolutely great. I love to hear that. Because it’s very, like you say, you’re using technology that is well understood. It’s available now. And now it’s just aligning the incentives to the outcomes. And I love you calling out also the value that farming provides that there is no financial recompense for at this time, and also to make sure that they understand that they are the incentives are aligned with the behaviors that we want, which, which I think is you had some fantastic call outs there. So it’s really great to hear those. You’ve talked a lot about what you’re currently working on? Seems like that’s starting to pick up some steam. So what are the biggest obstacles that you and your team are facing right now?

EMMA:

Man, one is just actually not that fun. It’s climate accounting. The guidance for how you map and track and give credit to all the companies that need or want to take credit for that is, is is a headache, and it’s moving slow. And that’s it’s hard. It’s complicated when you do get it right. But that’s I think causing a lot of when I talk about, you know, how do we make sure that buyers are showing up, provide that value for farms so that they start to orient towards delivering some services, those buyers themselves are feeling unsure of the quality of these offsets these credits, they’re buying the land? Will they be able to get credit for it? Right? If they spend money on this? Are they going to be able to tell their investors and meet their commitments to their investor groups that they’ve made on climate, and that slows things down? Because then if we don’t have a reliable source of value, we can’t go show up to farms and be like, you’re going to get paid, And then we turn around and be like, yeah, maybe it’s gonna be next year, right? Like, that just undercuts the speed at which we need to see this transition. So that stable source of value is impeded by this challenge. And a lot of the climate accounting, again, like it’s a hard problem, but we just need a stable policy environment, and one that really accelerates and clarifies the ways that these credits can count and the quality of them, because there’s a lot like, I look at the landscape myself. And I didn’t know the ins and outs of all these different programs, having thought a lot about the science. Gosh, like, you know, some people will say, like, what’s the one thing that you can do? It’s just like, oh, geez, I can’t even give you one thing, because it’s a complicated landscape that needs to go down, for sure to make this this easier on the buyer side.

often folks will say, Man, carbon offsets are not the solution, because what that’s gonna undercut people’s ability to cut their own emissions. To which, what, what I say strongly is that it’s not an either or, that if we are in an either or situation right now, with like, either you’re gonna cut your emissions, or you’re gonna buy offsets, you’re totally screwed, that it has to be everything, all of the above, right? If you read the last IPCC report, we’re going to need all of the emissions cutting, and we’re going to need all of the offsets. And so I really want to encourage folks from all sides of the aisle to not get committed to one thing, and I think there’s so much need for change, that buying a few offsets is not gonna actually insulate any of these companies from the need to reduce their emissions. I think that’s just and it slows down, it slows down these markets, which are going to take years to develop, and we don’t, we don’t have years anymore to develop these markets. So that’s, that’s a, that’s a, an anxiety provoking conversation of like, we just can’t choose between the two at this point.

SCOTT:

Yeah, I agree. 100%, I hope that people are starting to realize that it’s like all levers, all pedals being pushed to the point, right?

EMMA:

direct air capture nature based solutions, those are not in opposition, either. Everything. Let’s do it all the time. Yeah.

SCOTT:

All right, I’m ready to go to Glasgow.

SCOTT:

Emma, thanks for joining us. It’s been really great talking with you about sustainability and specifically environmental sustainability, and also agriculture. I can talk about agriculture for a long period of time now. I’ve really grown to appreciate it through my exposure, both to the people who are working on the commercial side of it, and also the farmers themselves. And so it’s, it’s a fascinating subject. And that really enjoyed hearing your take on it. And I really do. I love the energy and passion that you bring to it. And also just your very sort of pragmatic approach of what what can I do, what can we do now to help start moving things now to get things going? Right. I think that’s really critical, and addressing the many challenges that are facing us. So thanks for joining us, and good luck and hope that we talk to you again soon.

EMMA:

It’s been my complete pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Episode Wrap

SCOTT:

That’s a wrap for this week!

Thank you again to Emma Fuller of Corteva. Thank you Dr. Shange from Tuskegee University. We’ll include links to learn more about George Washington Carver, The Carver Integrative Sustainability Center, and much more at lookbothways.kinandcarta.com

This episode was written and produced by Maxx Parcell with limited quippery from me, Scott Hermes. Sound Engineering by Chris Mitchell. Original music by Ethan T Parcell and Lucas Parcell.

Follow us on instagram at lookbothwayspodcast and be sure to subscribe on your podcast dispenser of choice to not miss an episode. If you enjoyed this episode, please feel free to give us a 5 star rating. You can also leave a comment at lookbothways.kinandcarta.com. Or if you want to contact us in a carbon-negative manner, you can spell out a message in the row crop of your choice this Spring and we will be sure to pick it up from our Look Both Ways satellite in the Fall.

See you next episode!